Some very wise counsel here, not about which path to choose but about how to make the choice(s). Pay particular attention to the last paragraph.

Author: Susanna J. Sturgis

Crimson

Just found this gem by the author of The Glass Bangle, one of my favorite blogs. Eloquent, intensely visual poetry about writing, and about other things.

Go Set a Watchman

Plenty of people have reviewed or written about Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, but my friend and mystery writer Cynthia Riggs pinpoints what I think is the most important issue raised by the contrast between Watchman and the classic that grew from it, To Kill a Mockingbird: the importance of editing. Not just copy and line editing, but the kind of editing that sees the potential in a manuscript that isn’t “there” yet and then coaxes, browbeats, and otherwise persuades the writer to make it real.

It’s rare these days that a publisher will invest this kind of time and expertise in a book, especially a first novel. Writers have to do much of the work ourselves, with the help of workshops and writers’ groups and, if we’ve got the money and can find the right person, an editor. But it’s always possible to improve even the drafts that we’re sure are done.

To All Who Plan to Read or Have Read “Go Set a Watchman”:

Cynthia and Howie compare “Go Set a Watchman” with “To Kill a Mockingbird”

Cynthia and Howie compare “Go Set a Watchman” with “To Kill a Mockingbird”

photo by Lynn Christoffers

“Go Set a Watchman” was Harper Lee’s first book, and first books are usually unpublishable, as was “Watchman.” While it has brilliant writing in patches, it has inconsistencies, improbable passages, repetitions, unnecessary divergences, too much back story, ramblings, boring passages, too much overwriting, and almost every error a new writer can make.

Tay Hohoff, an editor at Lippincott, saw promise in the work, saying the “spark of the true writer flashed in every line.” She urged Harper Lee to scrap “Watchman” and start all over, write a new book with an entirely different story. Hohoff saw Scout’s young voice, one of several back stories in “Watchman,” as the potential for a great book once it was rewritten, and, of course…

View original post 208 more words

Stretching

The nice thing about poetry is that you’re always stretching the definitions of words. Lawyers and scientists and scholars of one sort or another try to restrict the definitions, hoping that they can prevent people from fooling each other. But that doesn’t stop people from lying.

Cezanne painted a red barn by painting it ten shades of color: purple to yellow. And he got a red barn. Similarly, a poet will describe things many different ways, circling around it, to get to the truth.

— Pete Seeger

I love this quote. Once upon a time poetry was one of my two word mediums. (Nonfiction was the other.) I loved working with traditional forms, especially sonnets, villanelles, and sestinas. They taught me to listen to the words, to say them out loud. Every word had to count, and I had to trust each word to do its job, all the while knowing that I couldn’t control exactly what it did once I let it go.

Gradually my lines got longer and longer. One multi-voice poem turned into a one-act play. From plays I slowly eased into fiction, though I’ve never ceased to think of myself as primarily a nonfiction writer.

It’s been a very long time since I tried to write a poem, but every day I draw on what writing poetry taught me: to listen to the words, to play with them, to let them play with each other.

Am I still “stretching the definitions of words”? Probably not. An essay can include many hundreds of words, a novel many thousands. Too much stretchiness causes ambiguity, which is fine in a work short enough to be read and reread several times but not so fine in a long work whose readers may accept the occasional detour but still expect forward motion.

Still, I do plenty of circling around in both fiction and nonfiction, less with the words themselves than with the images and scenes I create with them. They blend and they clash, they resonate and dissonate. (Two dictionaries think I made “dissonate” up — maybe I’m stretching words after all.) Sometimes they startle me.

Wrote Emily Dickinson, a master of the poet’s art:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Perhaps the truth really is too blinding to be faced directly. I have no idea. I’ll let you know when I find it. For now, exquisite precision doesn’t seem to be getting me any closer, so I’m putting my faith in slant and indirection.

Sturgis’s Law #4

This past spring I started an occasional series devoted to Sturgis’s Laws. “Sturgis” is me. The “Laws” aren’t Rules That Must Be Obeyed. Gods forbid, we writers and editors have enough of those circling in our heads and ready to pounce at any moment. These laws are more like hypotheses based on my observations over the years. They’re mostly about writing and editing. None of them can be proven, but they do come in handy from time to time. Here’s #4:

“The check’s in the mail,” “I gave at the office,” “All this manuscript needs is a light edit”: Caveat Editor.

If you’ve forgotten all the Latin you ever learned or never studied it in the first place, “Caveat” means, roughly, “Watch out!”

When someone tells you “The check is in the mail” or “I gave at the office,” your most likely response is skepticism. You know this because you have used variations on the same excuses yourself, right? I sure have.

When someone tells you “The check is in the mail” or “I gave at the office,” your most likely response is skepticism. You know this because you have used variations on the same excuses yourself, right? I sure have.

It is true that all some manuscripts need is a “light edit.” These manuscripts are generally prepared by fairly experienced writers who have already run them by a few astute colleagues for comments and corrections.

When I and most of the working editors I know roll our eyes at “All this manuscript needs is a light edit,” it’s because the manuscript in question usually needs considerably more.

So what does “light edit” mean?

Nothing associated with editing has one clear-cut, hard-and-fast, universally understood definition, but “light edit” generally means copyedit, as described in “Editing? What’s Editing?”:

Let’s say here that copyediting focuses on the mechanics: spelling, punctuation, grammar, formatting, and the like. With nonfiction, it includes ensuring that footnotes and endnotes, bibliographies and reference lists, are accurate, consistent with each other, and properly formatted.

Once one starts dealing with matters of style and structure — snarly sentences, internal inconsistency, abrupt paragraph transitions, missing information, and so on — one has moved beyond the realm of the light edit.

Most of us are not the best judges of our own work. Good writers know this. When we think a story or essay is done, the very best we can do, we set it aside for a week or a month. When we come back to it, we see it with fresh eyes. Problems we missed before are now glaringly obvious, from typos to dangling participles to plot holes that could swallow a truck. Often the fixes are just as obvious, thank heavens.

Outside editors come to the work with even fresher eyes, along with considerable experience in identifying and fixing problems in all sorts of manuscripts. They haven’t seen the previous drafts. They don’t know what you meant to say. They see only what’s there on the page.

So when you approach a prospective editor, don’t lead off with “All this manuscript needs is a light edit.” Describe the work and let the editor know what you want to do with it: submit it to a literary magazine or academic journal? find an agent? self-publish?

With a book-length work, fiction or nonfiction, an evaluation or critique is often the best place to start. Editing a book-length work takes time. This means it isn’t cheap. A good critique will point out the strengths of your ms. as well as any weaknesses that may exist. It will identify problems that you can fix yourself. It will let you know if this particular editor is a good match for you and your manuscript.

And if you’re an editor, the next time a prospective client approaches you with “All this manuscript needs is a light edit,” don’t snigger, raise your eyebrows, or roll on the floor laughing.

Because this time the author may be right.

Chicago Style

My library’s annual monster book sale was last weekend. Of course I went. Of course I came home with a stack of books, and all for $10.

The book sale takes place in the elementary school gym. All the sorting and shelving is done by volunteers.

The book sale is a browser’s heaven: tables and tables of books sorted, and occasionally mis-sorted, into general categories, and many with more books in the boxes underneath. I rarely go with a particular book in mind. I always find books I didn’t know I was looking for.

Or they find me.

Browsers cheerfully recommend books to total strangers, and sometimes get into spirited conversations about books they liked or books they thought were overrated. I was poring over one of the history-related tables, head cocked sideways so I could read the spines, when the fellow to my right handed a book to the fellow on my left. The book passing in front of me was The Chicago Manual of Style.

“Are you interested in this?” asked the fellow on the right, who I guessed (correctly) was the father of the fellow on the left.

My constant editorial companions. Clockwise from top: The Chicago Manual of Style, Words into Type, Amy Einsohn’s Copyeditor’s Handbook, and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary.

I’ve been on first-name terms with Chicago since 1979, when it was still called A Manual of Style. Could I remain silent while my old buddy and sometime nemesis changed hands right before my eyes? I could not. “That’s the current edition,” I said. “I’ve got it at home. I’m an editor by trade.”

Dad let on that Son was an aspiring writer. Son seemed a little uneasy with the description. “If you have any interest in mainstream publishing,” I said, “that’s a very good book to have.”

I don’t know whether they bought it or not, or what they paid for it. It was half-price day at the book sale, so probably not more than a buck or two. But if you have any interest in mainstream publishing, especially in the U.S., it is a very good book to have. Or you can subscribe to the online edition for $35 a year.

In U.S. trade and academic publishing, The Chicago Manual of Style is something of a bible. It contains almost everything writers and editors need to know about book publishing, along with extensive recommendations for further reading in various areas. It includes chapters on grammar, usage, and punctuation. At least half of its 1,026 pages are devoted — as its title might suggest — to style.

What is “style”? Think of all the myriad choices you make when you’re writing and especially when you’re editing your own work, about capitalization and hyphenation, about the use of quotation marks, boldface, and italics. How to treat titles of movies or titles of songs, and words from other languages, and the English translations of those words. And on and on and on. Style comprises all the decisions made about how to handle these things. “Chicago style” is a collection of particular recommendations. If you italicize book titles and put song titles in quotes, you’re following Chicago style, maybe without knowing it.

Much of the nit-pickery that goes into copyediting is about style. Confronted with the plethora of details that go into Chicago style, or Associated Press (AP) style (widely used by newspapers and periodicals), or American Psychological Association (APA) style (widely used in academic writing, especially the social sciences), the novice writer or editor may find it hard to believe that applying a particular style makes things easier — but it does. Every time I embark on editing a long bibliography, I am profoundly grateful to Chicago for its documentation style and to the authors who apply it consistently. I would hate to have to learn or invent a new documentation style for every bibliography I work on.

That goes for other aspects of style too. Following a style guide in effect automates the minute details and frees your mind to deal with the more interesting stuff like word choice and sentence structure and transitions between paragraphs.

The Chicago Manual of Style came into existence early in the 20th century as the style guide for the University of Chicago Press. Then as now, the press specialized in scholarly works, and the early editions of its style guide reflected that. Now it’s widely used by trade publishers, independent publishers, and self-publishers as well as academic presses.

What this means in practice is that not all of its recommendations are well suited to every type of book, and the further one gets from scholarly nonfiction — say, into the realms of fiction and memoir — the more cause one is likely to have for ignoring some recommendations and improvising on others. This is fine with Chicago‘s compilers but not so fine with some copyeditors, who treat the book’s style recommendations as Rules That Must Be Obeyed.

I think of them as Conventions That Should Be Respected, and Generally Followed in the Absence of a Sensible Alternative. I also advise serious writers to introduce themselves to Chicago style and even get to know it. Automate the petty details and you can focus your attention on the big stuff. You’re also more likely to win an argument with a stubborn copyeditor.

In Marilyn’s Kitchen

Word came last Friday that an old friend had passed. Years ago Marilyn had left Martha’s Vineyard, where I live, to return to her native Canada. She was a phone person; I’m not. I’m an email person; she wasn’t. Communication between us was sporadic, but we did manage to touch base at least once a year.

Marilyn was a retired teacher, and if anyone ever had a richer, more adventurous retirement I can hardly imagine it. She was a master of the fiber arts, spinning and weaving. She loathed Canadian winters and would usually spend the winter months in a warmer place, often in Central or South America, or in Goa, on the west coast of India. She’d come back with fabric ideas and stories about the people she met.

Marilyn was multi-talented. Along with spinning and weaving, she wrote wonderfully, sang in the same chorus I did, and made the world’s best chocolate chip cookies. She also had a genius for bringing together people who wouldn’t have connected otherwise. I was lucky enough to be one of them. She roped me into a group of women who gathered, usually in Marilyn’s kitchen but occasionally elsewhere, to write and share our writing.

Puppy Rhodry tangled up in Marilyn’s weaving, ca. February 1995. That’s me standing by.

A fire might be burning in the fireplace. Coffee was ready on the counter, a plate of chocolate cookies on the table, and not infrequently we’d have a nip of Black Bush on the side. My half-malamute dog Rhodry sometimes came along. Once when he was a puppy I forgot to keep an eye on him while we were writing. A thump from the living room brought us all out of our seats: little Rhodry had managed to get himself tangled up in one of Marilyn’s looms. I almost panicked, but Marilyn didn’t: she methodically disentangled the puppy from the precious weaving. Nothing was damaged. Then she insisted on recreating the scene so we could get a picture.

I’m an editor by trade and a writer by avocation, but I was hooked on computers by then. I typed on a keyboard and my words appeared on a screen. In Marilyn’s kitchen we wrote in longhand, in pen or pencil on yellow pads of paper. One of us would choose a word or a key phrase, set the timer for 10 or 15 or 20 minutes, and say “Go.” And we’d write write write till the timer went off.

Then we’d read what we’d written aloud to each other. No one had to read what she’d written, but we nearly always did. And what we wrote was amazing, sometimes startling, often beautiful or wry or laugh-out-loud funny, and sometimes all of it at once.

No one was more amazed than I. I’d fallen into the common writerly trap of thinking that writing was synonymous with suffering and angst, and especially that it was inevitably solitary. In Marilyn’s kitchen I learned otherwise. I learned that if I let myself go, I could cover two pages with words in 15 minutes or less, and that there would always be images and insights and whole anecdotes that I could then build on.

While working on my first novel somewhat later, I discovered that the surefire cure for writer’s block was to take pen and paper in hand and leave the computer behind. Later still, with first novel mostly done and me sinking into the writer’s equivalent of postpartum depression, I did Julia Cameron’s Artist’s Way workbook from beginning to end. Morning pages reminded me of the power of writing in longhand, and I’ve been doing most of my first-drafting that way ever since.

But the revelation first came in Marilyn’s kitchen, and another one too: that writing doesn’t always have to be a solitary struggle. Writing together can be exhilarating, and a reminder of what richness can pour from the pens of those who don’t consider themselves writers.

Top 10 Writing Tips

These are good. Several are probably more applicable to fiction than nonfiction, but most apply to all kinds of writing. My favorites are 1, 2, 3, 8, and 9. And maybe 10. I’m not sure about the love or the fun part, but the wonder of words coming through my fingertips? Yeah, that’s a big one. Thanks to Charles French‘s words, reading, and writing blog for the lead.

A few months ago I was asked by the Gold Coast Bulletin to come up with a list of writing tips that they could publish in their newspaper. I really wanted to include those tips in a blog post back then too, but the Bulletin asked me to wait until they’d published them first, which is fair enough. I’d pretty much forgotten about it, but this week my wonderful publicist tracked down the link for the whole article that they wrote up on me back in May in the aftermath of Supanova, which means I can now share my tips with you all!

Feel free to share the above tips if you find them helpful at all. And if you want to read the whole article (it’s an entire page, which is so cool!), you can do so by clicking on this link to find a screenshot JPEG of it here:

View original post 44 more words

Enough Notebooks

My regular writing time is from 7 to 9 a.m. I’m one of those insufferable people who’s wide awake and functional as soon as my eyes are fully open, and I don’t need coffee to do it. (I drink strong black tea with milk, no sugar, but only when I’m awake.) This morning I was a little late getting started because I’m reading an excellent book: Dorothy West’s The Wedding. I knocked off 20 minutes early because my longhand drafts and notes for Wolfie, the novel in progress, no longer fit in their notebook, and my other two notebooks are otherwise occupied.

Clearly a visit to the Staples website was in order.

Now the strict constructionists among you will not allow that the purchase of writing-related supplies constitutes “writing” for the purpose of “writing time,” and you may be right. However, being a writer, I can rationalize anything, and the pages spilling out of my notebook were messing up my head.

Dear readers, I ordered.

The Staples website is not as sensibly organized as it might be, so it took more than 20 minutes to find everything, even though I knew what I was looking for.

Some of the current pen collection

I do nearly all my first-drafting and most of my note-taking in longhand. On paper. Cut, Copy, and Paste don’t work on paper, but I still need to move things around, insert new pages between old ones, and (ideally) find some dimly remembered bit when it needs to be found. In my world folders do best in file cabinets, not lying around on desks and tables. I wanted notebooks. Three-ring binders might have worked, but I write with fountain pens and real ink-bottle ink and most punched or punchable paper can’t handle it.

Well, it can, but the ink often comes through to the other side, which means I can’t write on both sides of the paper. I am frugal, I am cheap. This wouldn’t do.

So a few years ago I spotted an ingenious notebook system in the Levenger catalogue. The Levenger catalogue is high-class porn for writer types, but it’s on the pricey side. Being frugal and cheap, I wasn’t willing to shell out for a system I didn’t know would work for me.

Open notebook with pocket divider. No, I could not live without Post-it notes.

Then I encountered something very similar at Staples, the Home Depot of office supplies. The price was reasonable enough to take a chance on. I splurged. The system, which Staples calls “ARC,” quickly became indispensable.

At left you can see what the notebooks look like. The binding comprises 11 plastic rings. The rings don’t open; the paper is punched with 11 holes, each one open so it can fit over the ring. Pages can be moved, singly or in chunks, from one place to another.

A custom 11-hole punch is available, so you can punch holes in any paper you like, but the paper that comes with the system is, wonder of wonders, sturdy enough for my fountain pens to write on both sides. And sturdy enough to be moved here and there several times.

So this morning I ordered three more notebooks — one with a leather cover (like the brown one in the photo) and two with polyvinyl (like the rose one) — and more dividers, some with pockets, some without.

“Blank paper,” I wrote last fall, “is faith in the future.” Enough notebooks, perhaps, is faith that what’s been written will be worth retrieving. Either way, I can’t wait for my order to get here.

Notes and More Notes

These days the how-to-write gurus like to divide writers into planners and pantsers. Planners, it’s said, outline everything in advance, then stick to the outline. Pantsers fly by the seat of their pants. They don’t know how the story is going to end until they get there. They make it up as they go along.

Either/or doesn’t work for me. Meticulous outlines make sense for some, but for me they suck the point out of writing. Writing is a journey of discovery. If I know in advance what I’m going to discover, why make the trip? I’m just a sightseer gazing through the windows of a tour bus.

Nevertheless, a story needs forward motion. To maintain forward motion, some sort of structure is required; otherwise you’ve got waves breaking on the shoreline, getting no higher than the high-water mark before they fall back, momentum spent. Last year I set a project aside because it had a surfeit of subplots, characters galore — and no forward motion whatsoever. I kept waiting for something to happen, but nothing did. What it lacked was structure.

Think of structure as the frame of a building or a road through previously untracked wilderness. Either way, your job is to build it. My first novel, The Mud of the Place, started with a character and a problem. I wrote it scene by scene. But though I never made an outline, I scribbled notes here there and everywhere. Years after I finished the final draft, I was still finding yellow pads with notes on them: notes about characters, notes about plot, notes about how I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.

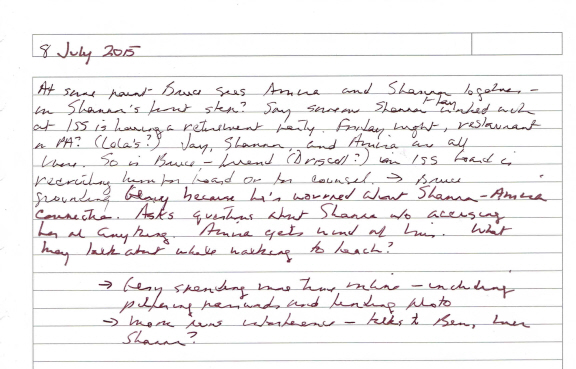

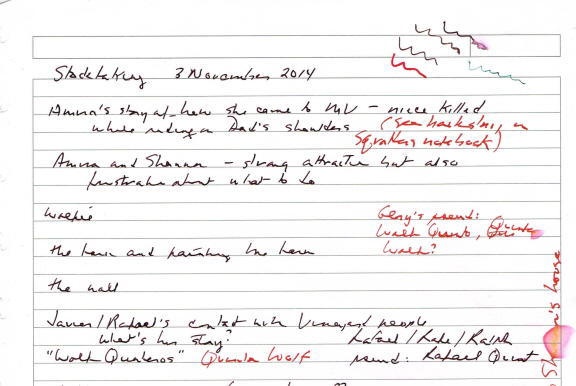

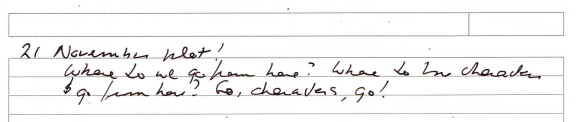

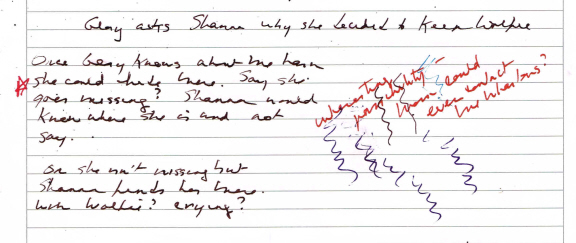

I’m doing the same thing with Wolfie, the novel in progress. Ideas and insights and solutions to plot problems often come to me while I’m walking or kneading bread or falling asleep, but to really explore and develop them I have to keep my hand moving across the page. This time I’m keeping the notes in one place, and in chronological order. When I’m stuck or drifting or just need a jump start, I dip back into them. My old ideas keep giving me new ideas.

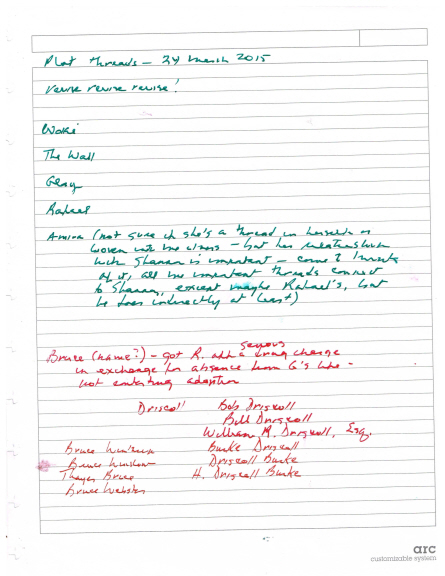

Here’s a sample of what they look like and what I use them for.

In early November I was trying to corral some emerging themes, subplots, and images. I was auditioning names for one character (Javier? Rafael? Rafe? Ralph?) and social media handles for another (for the moment she’s settled on Quinta Wolf). Note also the ink scribbles at the top and the liquid splotch (probably tea, maybe beer) at right. The red notes were added later.

Here the author is trying to figure out what the hell happens next. She does this a lot.

Toward the bottom of the same page, the pen offers an answer — and starts speculating about a possible plot development further down the road. I haven’t got there yet, so I don’t know how it’s going to play out. Note the scribbles. Note taking often involves scribbles.

By late February, I had started draft 2, even though I hadn’t finished draft 1. My main plot threads were clear and becoming clearer. I had to build them a trellis to climb on. On March 24, I listed the characters driving each of the threads. “The Wall” is a mural that protagonist Shannon is painting on her living room wall. It has, as these supposedly inanimate objects sometimes do, taken on a life of its own. Amira wandered in from the set-aside novel, where she plays a major role. Her role in Wolfie isn’t settled yet, but it’s definitely important.

At the bottom of the page I’m brainstorming names for my villain. He started off as Bruce McManus, which didn’t feel right. “Bruce” has stuck, but “McManus” is gone. I didn’t want a name with obvious ethnic associations. I did want a name that suggested that what this guy does, though terrible, can be and often is done by ordinary, unexceptional men. His surname is now Smith.

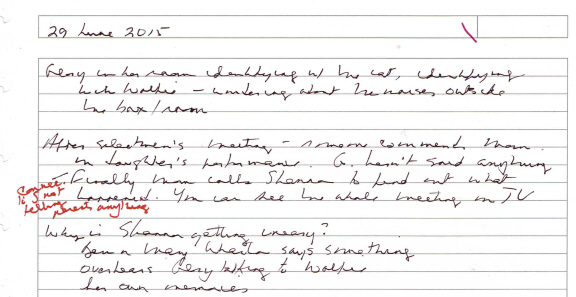

Here — not even three weeks ago! — I’m looking ahead to what follows a key scene (“selectmen’s meeting”). The scene itself is being lifted wholesale from draft 1, but when I first wrote it I hadn’t thought much about what its repercussions and aftershocks might look like. I’m also working out some character motivation: “Why is Shannon getting uneasy?” She is uneasy, and with good reason, but neither she nor I are quite sure why. The tricky thing is that it can’t be too obvious. One of the questions that’s driving this novel for me is “What do you do when you suspect something is very wrong, but you can’t be sure and the stakes are too high to allow for mistakes?” The jury’s still out on that one.

And finally, here’s the sketch for a plot break-through scene. Bruce, an outwardly rational lawyer who weighs the consequences of (almost) everything he contemplates doing, has to make a move that isn’t all that well thought out. He has to be, in other words, on the brink of panic. What would do it? Well, if he realized that Shannon, whom his 11-year-old stepdaughter, Glory, idolizes, knows Amira, who counseled Glory four years earlier when she was in trouble at school, that would do it. How to bring that about? I mulled that over on several walks, then a possibility popped into my head. On July 8, I sketched it out and decided, Yeah, that’ll work. Let’s try it.