The options for words beginning with X are so limited — even though X can stand for anything — that it’s tempting to go for a word that sounds like it begins with X: eXperience, eXpertise, eXpression, eXpurgate, eXcuses, and so on and on and on. Readers, I considered it.

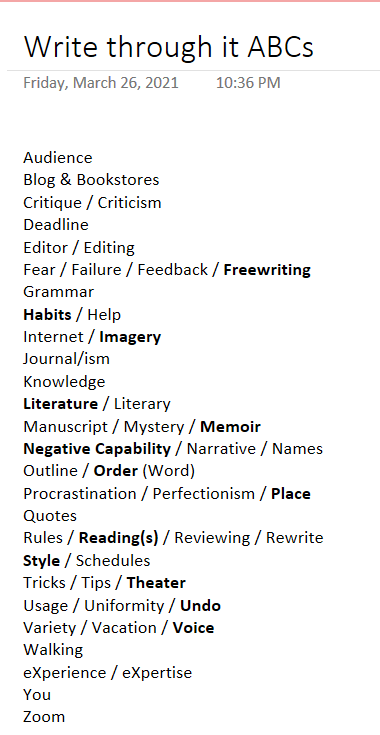

On the brink of April, with the Blogging A to Z Challenge in mind, I had started an A-to-Z list in Onelook. At first there were several blank lines, but they filled in pretty quickly so by mid-month it looked like the screenshot at left. The options I actually decided to blog about are in bold.

With the end of the month, and the end of the alphabet, drawing relentlessly closer, eXperience and eXpertise were the best I could come up with.

Then, while I was out walking the other day, what should come to mind but Xanadu. (I’m not kidding about the power of walking, people — and when it’s eXacerbated by the power of deadlines you’re talking about potentially major magic.)

Once upon a time I knew most of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan” by heart. The first five lines are as clear in my memory as ever, and the rest of it is so familiar as I reread it.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

I also remember how fascinated I was by the imagery when I read it for the first time, in English class my senior year of high school. A history buff with a more than passing acquaintance with the Middle East, I knew that Kubla Khan was Genghis Khan’s grandson but that was about it. I went looking for more about the River Alph (which doesn’t exist in our world) and demon-lovers (which may or may not exist) and Mount Abora (which doesn’t exist, but Coleridge may have meant Mount Amara, which does) and, of course, Xanadu itself (Kubla Khan’s summer palace). And that got me to marveling at how the poet had created such a vivid picture of the forest, the chasm, the “mighty fountain,” while making it clear that this “sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice” was a more than physical place.

The vision, I learned, had come to Coleridge in a dream — some commentators thought he might have been under the influence of opium — so of course I also learned about the “person on business from Porlock” who famously interrupted the poet while he was transcribing his dream onto paper.

Was this person from Porlock real, or had Coleridge hit an internal wall, a failure of nerve or of imagination? We’ll never know, and in any case this Porlockian intruder has taken on a life of his own. We’ve all been interrupted at our creative labors by an infinite variety of Porlocks. Porlock may come in person, or by phone, or text, or email, or private message. We’ve all probably gone to the door or phone or computer when no one was there, maybe hoping that someone was?

For me “Kubla Khan” is complete as is. It may not represent Coleridge’s whole dream, just as he couldn’t “revive within” himself the “symphony and song” of that Abyssian maid and her dulcimer, but it doesn’t have to. How often does a poem, a story, an essay, a novel, do everything we hoped and imagined it would when we started? Rarely, at least in my experience. But we wrap it up, send it out — and go on to the next.