I can revise, rewrite, and edit pretty much any time I’m awake, but for writing, especially early-draft writing, especially writing long and scary projects (like Wolfie, my novel in progress), I’m best in the morning, in the hour or two or three after I wake up.

I’m braver in the morning. I’m less easily distracted by the voices chattering inside my head and by whatever I’m supposed to do that day.

For several recent weeks my early-morning writing time was taken up by work, editing for pay and on deadline — my livelihood.

Another thing: When I’m working on a long and scary project, my mind is usually mulling it over while I’m out walking with my dog, or dropping off to sleep at night, or waking up in the morning. Mental logjams break up when I’m nowhere near my pens or my laptop.

During those several recent weeks, the jobs I was working on took up semi-permanent residence in my head. That’s what my mind kept mulling when I was out walking, or driving, or dropping off to sleep.

Blank paper is scary, but it’s full of potential. (That’s the scary part.)

In short, for about three weeks I did no work on the novel. I barely even blogged.

How to get back in the groove?

Starting is easy (ha ha ha). Blank pages are scary but they’re full of potential.

I’d recently started a second draft. The not-quite complete first draft is more than 225 pages long. (First draft = first draft prime: the real first draft is in longhand, and I always do a little revising as I’m typing it into Word.) When I tried to recall it, it was like looking through the wrong end of a telescope.

More to the point, I was sure that if I actually looked at it, I would realize it was crap. I have had this problem before. It’s why when I’m working on a long and scary project I look at it every day. Five minutes is enough. I don’t have to write anything. I just have to open the file and look at it.

Once I’ve opened it, I always find something to fiddle with, and after I’ve done a little fiddling, I nearly always write something new.

Wolfie‘s title character is a dog. So far the only cat in the story is Schrödinger’s, and of course I don’t know if that cat is alive or dead, real or unreal. Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment hypothesized a cat in a closed box with a vial of lethal radioactive material. The vial may or may not have broken; the cat may be alive or dead. I, outside the box, don’t know what has happened inside the box until I open it. Is the cat alive or dead?

I, sitting at my laptop, am dead certain the novel in progress is crap. If I actually look at it, I will know for sure it is crap and then what will I do with the rest of my life?

But it never works that way. It’s always

looking -> fiddling -> writing

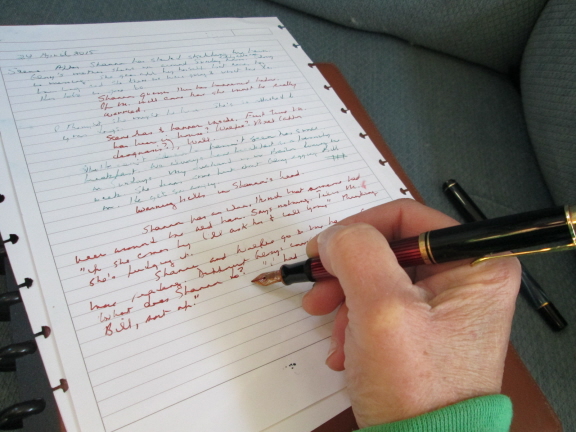

After I’d read a few pages of my second draft, the seed of a new scene took root in my head. The scene comes much later in the novel. I sketched it out in longhand then went back to reading.

So why the dead certainty that the writing has turned to crap in my absence? Interesting question, but it’s going to have to wait. I’m writing.

The moving hand writes and a scene takes root.

Writing and editing aren’t the same, but they both qualify as “demanding word work.” Over the last year or so, I’ve managed to maintain a pretty good balance: edit for five or six hours a day, write for up to two. The writer grabs the first two hours after waking, my absolute best creative time. (I’m an early riser, but my internal editor tends to sleep late. I’m also easily distracted by the events of the day once they start unfolding.)

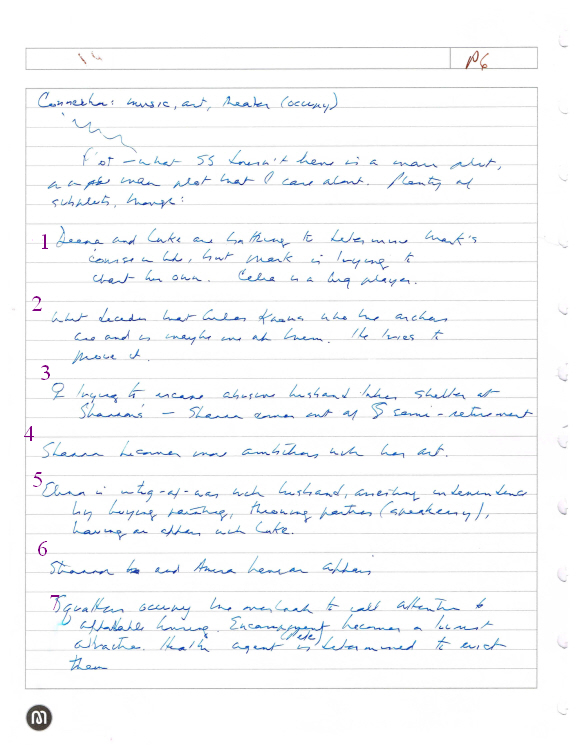

Writing and editing aren’t the same, but they both qualify as “demanding word work.” Over the last year or so, I’ve managed to maintain a pretty good balance: edit for five or six hours a day, write for up to two. The writer grabs the first two hours after waking, my absolute best creative time. (I’m an early riser, but my internal editor tends to sleep late. I’m also easily distracted by the events of the day once they start unfolding.) My #1 goal for my first novel, The Mud of the Place, was to show how the place I live in works. I live on Martha’s Vineyard. Martha’s Vineyard is in the news a lot, especially in the summer, especially when the president comes to visit. If you see Martha’s Vineyard on the news, you generally see what the reporters see: the summer resort, the quaint tourist attractions, the celebrities. I wanted to show what goes on backstage. The reporters and the summer people rarely see this stuff, and when they see it, they don’t really understand what’s going on.

My #1 goal for my first novel, The Mud of the Place, was to show how the place I live in works. I live on Martha’s Vineyard. Martha’s Vineyard is in the news a lot, especially in the summer, especially when the president comes to visit. If you see Martha’s Vineyard on the news, you generally see what the reporters see: the summer resort, the quaint tourist attractions, the celebrities. I wanted to show what goes on backstage. The reporters and the summer people rarely see this stuff, and when they see it, they don’t really understand what’s going on.

As usual, Ursula K. Le Guin got there long before me. Her Steering the Craft (Portland, OR: Eighth Mountain Press, 1998) is my favorite how-to book. Sometimes I open to a page at random, as if I were casting the I Ching or laying out tarot cards. The other day I was flipping through looking for advice on plot. This is what I found:

As usual, Ursula K. Le Guin got there long before me. Her Steering the Craft (Portland, OR: Eighth Mountain Press, 1998) is my favorite how-to book. Sometimes I open to a page at random, as if I were casting the I Ching or laying out tarot cards. The other day I was flipping through looking for advice on plot. This is what I found:

“We are each other’s angels” goes the song. My teeth start itching at any reference to angels. There’s something about the concept that makes smart people start babbling in clichés. But OK, point taken: we are each other’s guides, teachers, helpers, and so on. But if we’re each other’s angels, we’re also each other’s devils, roadblocks, obstacles. When a character is the hero of her own story but the villain in someone else’s — that’s where things get interesting.

“We are each other’s angels” goes the song. My teeth start itching at any reference to angels. There’s something about the concept that makes smart people start babbling in clichés. But OK, point taken: we are each other’s guides, teachers, helpers, and so on. But if we’re each other’s angels, we’re also each other’s devils, roadblocks, obstacles. When a character is the hero of her own story but the villain in someone else’s — that’s where things get interesting.