It’s happened to me many times over the years, and to many other editors I know: Someone calls, or emails, or comes up to me at a social gathering and asks, “How much would it cost to proofread my novel?”

Or “my [fill-in-the-blank]”: memoir, thesis, dissertation, résumé, website, whatever.

I quickly learned that what the writer invariably wants is editing, not proofreading.

Proofreading is the last step before publication. As I wrote in “Editing? What’s Editing?,” of all the levels of editing, proofreading “is the most mechanical of all. It means catching the errors that have slipped through despite all the writer’s and editor’s best efforts.”

To proofread something that hasn’t been adequately edited is an exercise in hair-tearing frustration. Of the gazillion things that need fixing, I can only fix the ones that are flat-out mortifyingly wrong. I learned long ago to say, “No, I’m sorry, I can’t proofread your manuscript. I think what you’re really looking for is an editor.”

At the moment, though, I’m in the middle of a proofreading job. Five papers that will be published in an economics journal. They’ve been edited. They’re dense, technical, but clearly written. I’m no economics expert. I don’t know the jargon. I’m looking for typos and grammatical errors. Since the journal publisher wants consistency across the five papers, I’m also looking to apply the journal’s house style. Taylor Rule or Taylor rule? Macroprudential or macro-prudential? Either option is correct, but the journal prefers “Taylor rule” and “macroprudential.”

At the moment, though, I’m in the middle of a proofreading job. Five papers that will be published in an economics journal. They’ve been edited. They’re dense, technical, but clearly written. I’m no economics expert. I don’t know the jargon. I’m looking for typos and grammatical errors. Since the journal publisher wants consistency across the five papers, I’m also looking to apply the journal’s house style. Taylor Rule or Taylor rule? Macroprudential or macro-prudential? Either option is correct, but the journal prefers “Taylor rule” and “macroprudential.”

When I started editing and proofreading in the 1970s, every copyedited manuscript had to be typeset from scratch. So proofreading meant reading the proofs — the typeset copy that would be laid out to produce the print-ready pages — against the manuscript. This could be a two-person job: one would read the ms. aloud and the other would mark the proofs. We’d read the punctuation and stylings as well as the words: “Jack pos S” meant “Jack apostrophe S” or “Jack’s.”

Proofreaders who worked solo developed the knack of reading proof against ms. and noting all discrepancies. I got to be pretty good at it, but I’m not sure I could do it now. Thanks to the digital revolution in publishing, I haven’t had to for a long time. These days the writer turns in an electronic file — usually in Microsoft Word, the editor works in Word, the copyeditor works in Word, the author reviews the edited file in Word, and eventually the Word file becomes the raw material for the proofs. Each version is cleaner than the one before it.

As a result, much proofreading these days is “cold” or “blind” proofreading. This is what I’m doing with the economics papers: reading the proofs without comparing them to any previous version. In effect, there’s no previous version to compare them to: the previous versions have all been incorporated into the proofs I’m reading.

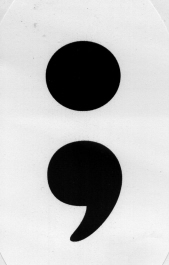

When I’m proofreading, I don’t read the same way as I do when I’m copyediting, or editing, or critiquing, reviewing, or reading for pleasure. The biggest difference is focus. I’m excruciatingly focused on the text letter by letter, word by word. It’s exhausting. When my attention shifts into phrase-by-phrase or sentence-by-sentence mode, I have to pull it back. Otherwise I’ll miss the misspelled word, the double “the,” the semicolon cheek-by-jowl with a comma where only one is needed.

When I’m proofreading, I don’t read the same way as I do when I’m copyediting, or editing, or critiquing, reviewing, or reading for pleasure. The biggest difference is focus. I’m excruciatingly focused on the text letter by letter, word by word. It’s exhausting. When my attention shifts into phrase-by-phrase or sentence-by-sentence mode, I have to pull it back. Otherwise I’ll miss the misspelled word, the double “the,” the semicolon cheek-by-jowl with a comma where only one is needed.

If you’re a crackerjack speller and know your punctuation cold, you can learn to proofread, but it’s going to take plenty of practice before you can do a creditable job. And the usual caveats apply to proofreading your own work: if you can possibly avoid it, do; but if you can’t, leave a week or two between the editing and the proofreading. What makes copyediting or proofreading your own work such a challenge is that you know what it’s supposed to say. If your character is named Jack, you’re going to see “Jack” on the page — even when it says “Jcak.” If you’ve been misusing a word all your life, you’re not going to be able to call the error to your attention.

If you’re not a crackerjack speller and if your punctuation skills are less than stellar, you do need a good proofreader. Trust me on this.

It gets worse when they learn you’re a writer, a teacher, or (gods forbid) an editor. Some people laugh nervously. Others clam up.

It gets worse when they learn you’re a writer, a teacher, or (gods forbid) an editor. Some people laugh nervously. Others clam up. Readers and writers, teachers and editors, are forever getting them mixed up with rules. How to tell a rule from a shibboleth? Rules usually further the cause of clarity: verbs should agree with their subjects in number; pronouns should agree with the nouns they refer to. Shibboleths often don’t. No surprise there: their main purpose isn’t to facilitate communication; it’s to separate those who know them from those who don’t.

Readers and writers, teachers and editors, are forever getting them mixed up with rules. How to tell a rule from a shibboleth? Rules usually further the cause of clarity: verbs should agree with their subjects in number; pronouns should agree with the nouns they refer to. Shibboleths often don’t. No surprise there: their main purpose isn’t to facilitate communication; it’s to separate those who know them from those who don’t. Hoo boy, did I go wild or what. Anyone who hadn’t mastered the which/that distinction was an ignoramus. I got to look down my snoot at them. I got to educate them.

Hoo boy, did I go wild or what. Anyone who hadn’t mastered the which/that distinction was an ignoramus. I got to look down my snoot at them. I got to educate them.

Along with the T-shirt I bought two oval semicolon stickers, one for my car, the other for the semicolon hater in my writers’ group. She accepted hers with grace but promptly drew an international “NO” symbol on it with a red Sharpie.

Along with the T-shirt I bought two oval semicolon stickers, one for my car, the other for the semicolon hater in my writers’ group. She accepted hers with grace but promptly drew an international “NO” symbol on it with a red Sharpie.