The Gay Head Cliffs, seen from the observation area.

Two days before the late January snow fell, I drove all the way to Aquinnah to see the Gay Head Cliffs. My Alaskan malamute, Travvy, rode shotgun, his nose usually as far out the window as it could get.

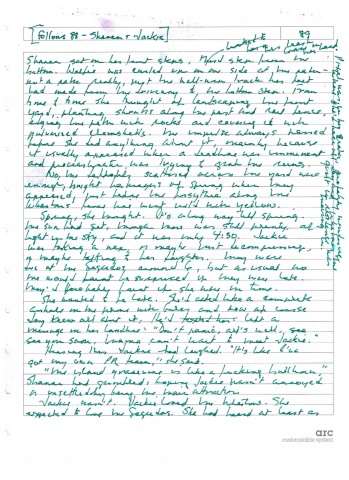

In the Forester’s back seat were two of my characters, protagonist Shannon and her long-estranged sister Jackie. Shannon’s in her mid-fifties. Jackie’s three years younger. They survived their violently alcoholic family in different ways, Shannon by fleeing, Jackie by sticking it out. After almost four decades of minimal contact, it’s Thanksgiving weekend and Jackie has come for a visit.

I live on, and write about, Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts. Martha’s Vineyard is famous, not least because the president and one of his recent predecessors vacation here. I write about the place and the people who are still here when the celebrities leave.

The Gay Head lighthouse. In a major engineering feat last fall it was moved 129 feet back from the cliff that was eroding out from under it.

The Gay Head Cliffs are celebrities in their own right, celebrities who never leave. People who know nothing else about Martha’s Vineyard have seen them in photographs. Shannon, like me and many another year-round resident, is somewhat jaded about both celebrities and tourist attractions, but she’s showing her sister around and it’s late November: no chattering crowds, ample places to park.

At this point I realized that my mental image of the cliffs looked like a picture postcard. I hadn’t been there in years. I couldn’t remember the path down to the beach or what the beach looked like. Hence this mid-January expedition. I kept my eyes on the road, occasionally scratched Travvy’s back, and listened to Shannon and Jackie talking in the back seat.

After I parked the car — there was no shortage of available space — we walked past the silent summer shops and up to the observation area. Shannon and Jackie leaned on the post-and-rail fence. Shannon pointed out over the water. “That’s Devil’s Bridge,” she said. “Major hazard to navigation.”

Jackie shaded her eyes against the sun and squinted. “I can’t see anything,” she replied.

“Neither can the ships,” said Shannon.

Most Vineyard people know about the wreck of the City of Columbus, a passenger steamship bound from Boston to Savannah. It ran aground on Devil’s Bridge, a submerged rocky shoal, in the dark early hours of January 18, 1884, and quickly sank. Despite heroic rescue efforts that morning by the Gay Headers and the crew of a passing vessel, 104 died; only 29 were rescued.

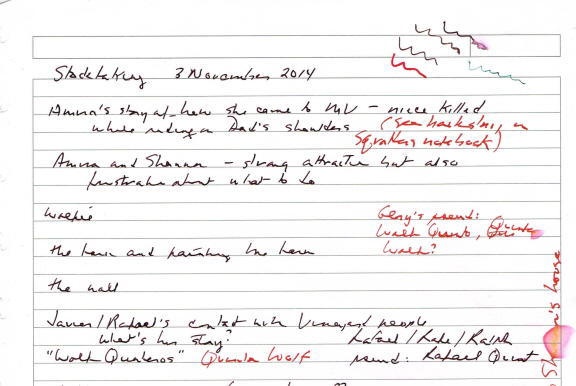

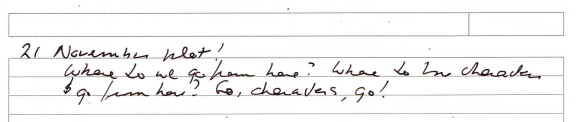

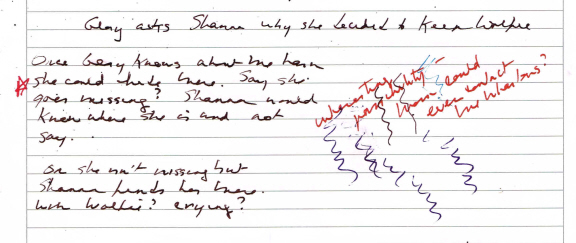

The anniversary had just passed when we drove to Aquinnah, so it was on my mind, but when Shannon said “Neither can the ships,” I froze. Rescue is a major theme in my novel in progress, starting with the rescue of Wolfie, the title character, who was inspired by (you guessed it) Travvy — rescue and the difficulty of recognizing threats before it’s too late. And there it was, arising naturally and unobtrusively from the place where my characters stood.

Every story, remembered or made-up, takes place somewhere. Where it takes place affects what takes place, deeply, profoundly, deeply, indelibly. Characters, both fictional and nonfictional, are deeply affected by where they are and where they’ve come from. Images, characters, and whole plots grow out of the soil they take root in.

Regional writing, writing deeply rooted in place, sometimes gets a bad rap. Regional writing is only about that region, so the thinking goes. It’s not universal. (If this reminds you of the equally popular notion that writing about women is only about women, and writing about people of color is only about people of color, while writing about white men is universal — it should.)

If William Blake could “see a World in a Grain of Sand,” writers can find a whole world in a particular place, and readers can learn more about their world from following a writer’s words into places they’ve never been.

For another take on where imagery comes from, check out my earlier blog post “Grow Your Images.”

The path to Moshup’s Beach is a lot longer and wider than I remembered. That’s my sidekick, Travvy, waiting for me to put the camera away and keep walking.

Once I realized how rocky the beach was, it was easier to hear what Shannon and Jackie were saying as they picked their way over the rocks.