“Omit needless words.” You’ve heard it, right? Maybe you’ve had it drummed into your head. It comes from Strunk and White’s famous, or infamous, Elements of Style. (More about that below.)

It’s actually pretty good advice. The tricky part is “needless.” What’s necessary and what isn’t depends on the kind of writing, the intended audience, and what the author had in mind, among other things. Consider, for example, “she shrugged her shoulders.” Taken literally, “her shoulders” is redundant — what else would she shrug? And sometimes “she shrugged” is fine. Other times, the mention of “her shoulders” emphasizes the physical aspect of the gesture, or influences the pacing of the sentence. “She shrugged” and “she shrugged her shoulders” read differently. Ditto “he blinked” and “he blinked his eyes.”

Unless you’re writing technical manuals (do people ever shrug or blink in technical manuals?), you don’t want an editor who lops off “eyes” and “shoulders” just because they’re literally redundant.

However, I do a lot of lopping off when I reread anything I’ve written. Words that served a purpose in the writing may turn out to be needless in later drafts — like the ladder you climbed in order to repaint a windowsill, they can be removed when the job is done. Nearly every draft I write is shorter than its predecessor.

Here’s an example from my novel in progress. Pixel has already been introduced as an elderly dog. Shannon is her owner, Ben their next-door neighbor.

Pixel descended the stairs with a confidence that Shannon hadn’t seen in weeks and thought might be gone for good, then trotted sprily over to Ben. Shannon followed, smiling. “Every summer I think she’s gone over the hill for good,” she said, “and with the first whiff of fall she always seems to drop a couple of years.”

Rereading, my eye balked at “and thought might be gone for good.” Wasn’t that covered by Shannon’s remark “I think she’s gone over the hill for good”? Sure it was. I struck out the needless words:

Pixel descended the stairs with a confidence that Shannon hadn’t seen in weeks and thought might be gone for good, then trotted sprily over to Ben. Shannon followed, smiling. “Every summer I think she’s gone over the hill for good,” she said, “and with the first whiff of fall she always seems to drop a couple of years.”

When I read it over, I didn’t miss those words at all, so the paragraph now looks like this:

Pixel descended the stairs with a confidence that Shannon hadn’t seen in weeks, then trotted sprily over to Ben. Shannon followed, smiling. “Every summer I think she’s gone over the hill for good,” she said, “and with the first whiff of fall she always seems to drop a couple of years.”

When I’m editing, either my own work or someone else’s, I’m always looking for what a workshop leader once called “soft ice” — words that don’t bear weight. What’s soft and what isn’t, and how soft is it, is a judgment call. I may go back and forth several times in five minutes about how soft — how needless — a word or phrase or whole sentence is.

In a current job, a memoir by a very good writer, I came upon this sentence:

As we came around the last curve, we were greeted by a scene of absolute devastation.

No problem, I thought. A couple of sentences later, I slammed on the brakes and backed up. How about this?

As we came around the last curve, we were greeted by a scene of absolute devastation.

I liked it. What the narrator saw was devastation, not a scene; “devastation” is a stronger word. But it’s the author’s call. She can stet “a scene of” if she prefers it that way.

* * * * *

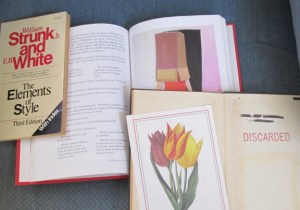

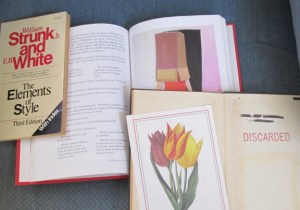

While writing the above, I went looking for my copy of The Elements of Style. To my surprise, I had not one, not two, but three copies. The little paperback I probably bought myself. The illustrated version, published in 2005, was a gift. So was the decommissioned library edition. The name of the library was effectively redacted, but concealed within the book’s pages were cards from two former colleagues. One of them had given it to me as a parting gift when I left my newspaper job in 1999.

Strunk & White times three

If you Google “strunk and white,” you’ll find that many love The Elements of Style and many, including some heavy-hitting grammarians, hate it. As I flipped through it for the first time in umpteen years, I was surprised by how much useful stuff it has in it. Yes, the tone is often prescriptive: Do it my way or else. No, it doesn’t apply equally to all kinds of writing. But it’s useful.

Strunk and White’s biggest drawback lies not within its pages but within its users. They turn guidelines into godlines, thou shalts and thou shalt nots that must not be disobeyed. This happens to The Chicago Manual of Style and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary too, among other reference books, so I know for sure it’s not entirely the book’s fault. When the godliners are teachers or editors, the damage they do can have a half-life of decades.

But this is no reason to jettison the books themselves. Read them. Experiment with their advice. Argue with it. Above all, take what you like and leave the rest.

And run like hell from anyone who insists you swallow them whole.

charles french words reading and writing

From a distance they looked like the same four buses — not only do school buses look alike, big, long, and bright yellow, but they look a lot like they did when I was a kid back in the Pleistocene. But they weren’t the same buses. Each bus has a number. Last year the regulars were 121, 123, 124, and 117H. This year 124 is back, but with different companions: 125, 126, and 116H.

From a distance they looked like the same four buses — not only do school buses look alike, big, long, and bright yellow, but they look a lot like they did when I was a kid back in the Pleistocene. But they weren’t the same buses. Each bus has a number. Last year the regulars were 121, 123, 124, and 117H. This year 124 is back, but with different companions: 125, 126, and 116H.

Editing and writing are closely related, but they aren’t the same. Writing creates something new. Editing rearranges, refines, and otherwise messes with something that’s already been created.

Editing and writing are closely related, but they aren’t the same. Writing creates something new. Editing rearranges, refines, and otherwise messes with something that’s already been created. Stylistic editing. This is called all sorts of things, including content editing, line editing, and copyediting. Here you go through the work line by line, asking whether each sentence, phrase, and word says what you want it to say, and in the best way possible. English is a wonderfully flexible language. Choosing the right word and putting it in the right place can make a big difference. Writers’ groups and volunteer readers (aka “guinea pigs”) can be invaluable here. You know what you meant to say, but until you get feedback from readers it’s hard to know how well it’s coming across.

Stylistic editing. This is called all sorts of things, including content editing, line editing, and copyediting. Here you go through the work line by line, asking whether each sentence, phrase, and word says what you want it to say, and in the best way possible. English is a wonderfully flexible language. Choosing the right word and putting it in the right place can make a big difference. Writers’ groups and volunteer readers (aka “guinea pigs”) can be invaluable here. You know what you meant to say, but until you get feedback from readers it’s hard to know how well it’s coming across. Copyediting. I hire out as a “copyeditor,” but my work includes plenty of stylistic editing so I have a hard time distinguishing one from the other. Let’s say here that copyediting focuses on the mechanics: spelling, punctuation, grammar, formatting, and the like. With nonfiction, it includes ensuring that footnotes and endnotes, bibliographies and reference lists, are accurate, consistent with each other, and properly formatted.

Copyediting. I hire out as a “copyeditor,” but my work includes plenty of stylistic editing so I have a hard time distinguishing one from the other. Let’s say here that copyediting focuses on the mechanics: spelling, punctuation, grammar, formatting, and the like. With nonfiction, it includes ensuring that footnotes and endnotes, bibliographies and reference lists, are accurate, consistent with each other, and properly formatted.