I seem to have taken up semi-permanent residence in Revisionland. Not only am I working on draft 3 of Wolfie, my own novel in progress, my recent jobs have included two critiques of first novels and a line edit whose structure needs a little tweaking. Editor that I am, with a fair amount of reviewing experience under my belt, I love revising and rewriting and recommending what other writers might do to improve their current drafts.

Most mornings I begin my writing session by lighting a candle or two, then picking The Writer’s Chapbook* from the table on my right, opening it at random, and reading the first quote that catches my eye. This morning the book opened to the “On Films” section, and my eye fell on a lengthy quote by novelist and screenwriter Thomas McGuane. After noting that in the novels of William Faulkner (“who frequently had his shit detector dialed down to zero”) “wonderful streaks” often alternate with “muddy bogs” that need to be slogged through, he continues:

Everyone agrees that Faulkner produced the greatest streaks in American literature from 1929 to 1935 but, depending on how you feel about this, you either admit that there’s a lot of dead air in his works or you don’t. After you’ve written screenplays for a while, you’re not as willing to leave these warm-ups in there, those pencil sharpenings and refillings of the whiskey glasses and those sorts of trivialities. You’re more conscious of dead time. Playwrights are even tougher on themselves in this regard. Twenty mediocre pages hardly hurt even a short novel but ten dead minutes will insure that a play won’t get out of New Haven.

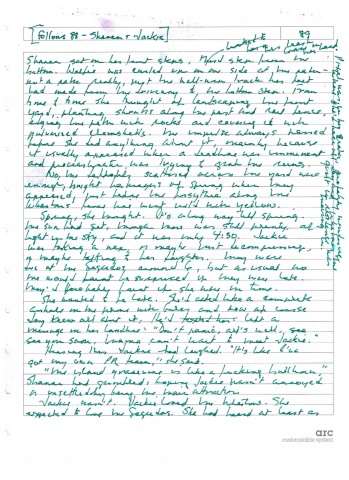

Me (right) in rehearsal, spring 1994, Vineyard Playhouse.

From the mid-1980s till the end of the 1990s, I was very involved in community theater, mostly as a stage manager, actor, or reviewer. (No, I did not review plays I was involved in. However, I often reviewed plays directed or acted in by people I knew. This taught me tact. Whole other subject. I’ve written about reviewing before — see “Reviewing Isn’t Easy” — and surely will again.) No surprise, then, that when I’m writing fiction, I often feel like I’m blocking scenes or directing them and that my characters are doing improv up on stage.

Both of the first-novel manuscripts I critiqued recently hold plenty of promise, but both are currently weighed down with loaded with dead air. In both cases, much of the dead air is dialogue. To both authors I suggested: “Imagine you’re watching these scenes on a stage. Read them out loud. How long before you start to doze off, fidget, or throw tomatoes?”

A novel might survive “twenty mediocre pages,” as McGuane suggests, but five pages of dead air might well be fatal, especially if they come near the beginning, and especially if you’re a first-novelist trying to get past one of the gatekeepers: agent, publisher, reviewer, or even readers willing to give unknown writers a chance.

Put your talking, puttering-about characters up on stage or on a movie screen. How long would you sit still?

* * * * *

*The Writer’s Chapbook: A Compendium of Fact, Opinion, Wit, and Advice from the 20th Century’s Preeminent Writers, ed. George Plimpton (New York: Penguin, 1989). I’ve got the revised, expanded version of the first edition. A completely overhauled edition was published in 1999, including some of the original excerpts but also more quotes from more recent and more diverse writers. Both editions are out of print but used copies can be found. That’s how I got mine. Highly recommended.

What does this have to do with writing and editing? I’m so glad you asked. As an editor, I sometimes hear editors complaining about writers who snark about their edits. As a writer, I sometimes hear writers complaining about the editors who butchered their manuscript and messed with their voice. Just about all of us have had occasion to bitch about agents, editors, and publishers who were too obtuse, lazy, illiterate, racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-genre, anti-literary, and/or obsessed with the bottom line to give our work a fair shake.

What does this have to do with writing and editing? I’m so glad you asked. As an editor, I sometimes hear editors complaining about writers who snark about their edits. As a writer, I sometimes hear writers complaining about the editors who butchered their manuscript and messed with their voice. Just about all of us have had occasion to bitch about agents, editors, and publishers who were too obtuse, lazy, illiterate, racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-genre, anti-literary, and/or obsessed with the bottom line to give our work a fair shake.

Anna Leahy

Anna Leahy  George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”