I’m in deep revision mode on Wolfie, the novel in progress, so ‘ve been thinking a lot about how I know what needs to be added or subtracted or completely rewritten. The truth is, I don’t know. In an early Write Through It post, I write that editing was “Like Driving.” Revision is like that too.

Early this year, I started a second draft before I’d finished the first. As I blogged in “On to Draft 2!” a couple of plot threads had emerged in the writing. Those threads were going to affect the novel’s climax and conclusion, but until I developed them more fully I wouldn’t know how.

A sound foundation

The same thing happened with my first novel, The Mud of the Place. I thought I was writing a tragedy. Then around page 300 of the first draft, a minor character said something that took me by surprise. Suddenly I could see a way out for a main character who was digging himself deeper and deeper into a hole. I tried to keep going — “I’ll fix the first 300 pages in the next draft,” I told myself — but I couldn’t. It was like building a house on a crumbling foundation.

So I went back to the beginning and started again. The rewriting wasn’t as hard as I’d feared. I didn’t have to throw everything out. That minor character’s words revealed new possibilities in the story that was already unfolding; they’d always been there, but I hadn’t noticed.

Since I can’t tell you how to revise, I’ll start by telling you how not to revise: Don’t return to page one and immediately start fiddling with punctuation and word choice. Revision starts with the big picture: structure, organization, plot and character development, that sort of thing. The little stuff is frosting on the cake. Mix the batter and bake the cake first.

To see the big picture, you have to step back — to approach your own work as if you’ve never seen it before. Of course you have seen it before, but if you let it sit for a while — a couple of weeks, maybe even a couple of months — you may be amazed how different it looks when you come back to it.

While you’re letting it sit, start a new project or wake up one that’s gestating in a notebook or computer file somewhere. If nothing tempts you, use your usual writing time to scribble whatever pops into your head. Chances are it’ll lead somewhere interesting.

If the work is far enough long, you might even draft a colleague or two to read and comment on it at this point. We all have different ideas of when the best time is to do this. I generally wait till I’ve gone as far as I can on my own.

When you’re ready, save your current draft with a new filename. The old draft is your safety net. Then start reading. Read like a reader or a reviewer — and not the kind of reader who pounces on every typo! Notice where you get impatient, or confused, or curious. I’m always on the alert for clues that something interesting is happening offstage. This is like walking by a closet and suddenly there’s loud pounding and thumping coming from behind the closed door. Something is demanding to be let out. See “Free the Scene!” for more about this.

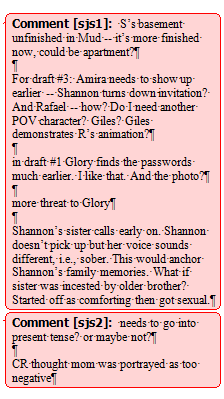

Word’s Comments feature is a handy way to make notes for revision. Here I’m looking forward to draft #3 while working on #2.

Make notes as you’re working about scenes that need trimming, or expanding, or moving to somewhere else. If you know what needs doing, go ahead and do it. Microsoft Word’s Track Changes feature enables you to make tentative additions and deletions, then revisit them later.

Look for “soft ice” — the words, sentences, and whole paragraphs that don’t carry their own weight. Look for the pathways that led you into a scene but that become less important once you know where you are. They’re like ladders and scaffolding: crucial to the construction process, but dispensable when the job is done.

You’ve heard the standard advice “Kill your darlings,” right? It means different things to different people, and I’ve got mixed feelings about it. I’ve got mixed feelings about most “standard advice.” Most of it’s useful on occasion, but none of it is one-size-fits-all. Take what you like and leave the rest.

But sooner or later when you’re revising you will come to a stretch of drop-dead perfect dialogue or a scintillating anecdote and realize that it just doesn’t belong in the manuscript. Maybe it’s too much of a digression. Maybe it calls too much attention to itself. Maybe it duplicates something better said earlier. It’s hard to let these things go. Track Changes comes in especially handy here. You can zap it provisionally and gradually get used to the idea that it really does have to go.

When you’re slash-and-burning and filling in gaps, don’t worry too much about the transitions between paragraphs and scenes. If the right segue comes to you, by all means go with it, but if it doesn’t, move on. You can smooth it out later.

If you can’t solve a problem while you’re staring at it, stop staring, make a note, and move on. My thorniest problems tend to solve themselves when I’m out walking or kneading bread, falling asleep or just waking up. Solutions sometimes appear for problems you haven’t come to yet. Writing is weird.

When I started draft #2, I swore I’d get to the end before I started draft #3, but now, at page 238, I’m pretty sure I won’t. At present I’ve got two viewpoint characters. To develop an important but currently underdeveloped plot thread, I need to add a third. He’s already a player, but adding his point of view is going to change the book’s balance a lot.

There’s also an incident I need to stage near the beginning of the book: my central character, Shannon, listens to an answering-machine message from her long-estranged younger sister. Shannon never picks up or returns these calls because her sister is always drunk or strung out. This time, however, her sister sounds sober and lucid. Shannon doesn’t pick up this time either, but the call ripples through the narrative. The ripples were already there; I just didn’t know what had prompted them.

So I’ve got a little farther to go in draft #2, then it’s back to the beginning to start on draft #3.

When someone tells you “The check is in the mail” or “I gave at the office,” your most likely response is skepticism. You know this because you have used variations on the same excuses yourself, right? I sure have.

When someone tells you “The check is in the mail” or “I gave at the office,” your most likely response is skepticism. You know this because you have used variations on the same excuses yourself, right? I sure have. No, I’m not a sports fan, but my fascination with the Vineyard and anything related to race and class is insatiable, so I had such hopes for this book. Class is a shifty thing on Martha’s Vineyard. It doesn’t look like what one reads about in textbooks or sees in urban areas. Here, as elsewhere in the U.S., we bend over backwards to avoid seeing it. It’s complicated by the distinction between the year-round population and the “summer people”; by the ethnic groups with deep roots here (especially Wampanoag, Anglo, Portuguese, and Cape Verdean); and by the long history of African Americans on the island.

No, I’m not a sports fan, but my fascination with the Vineyard and anything related to race and class is insatiable, so I had such hopes for this book. Class is a shifty thing on Martha’s Vineyard. It doesn’t look like what one reads about in textbooks or sees in urban areas. Here, as elsewhere in the U.S., we bend over backwards to avoid seeing it. It’s complicated by the distinction between the year-round population and the “summer people”; by the ethnic groups with deep roots here (especially Wampanoag, Anglo, Portuguese, and Cape Verdean); and by the long history of African Americans on the island. The web doesn’t impose space limits. Bloggers and others writing for the web could theoretically go on forever — but we don’t. Paradoxically perhaps, when it comes to the web the standard advice is “keep it short.” We could go on forever, but most readers won’t stick with us that long. There are limits, but they aren’t spatial.

The web doesn’t impose space limits. Bloggers and others writing for the web could theoretically go on forever — but we don’t. Paradoxically perhaps, when it comes to the web the standard advice is “keep it short.” We could go on forever, but most readers won’t stick with us that long. There are limits, but they aren’t spatial.

Consulting the town’s zoning bylaws — the scene takes place in the town I live in — I discovered that the snow fencing didn’t violate any bylaws, but this wouldn’t stop some of the busybodies I’ve run into in my time. I also decided that she wasn’t actually on the conservation commission. She had appointed herself guardian of the character of a neighborhood she didn’t even live in.

Consulting the town’s zoning bylaws — the scene takes place in the town I live in — I discovered that the snow fencing didn’t violate any bylaws, but this wouldn’t stop some of the busybodies I’ve run into in my time. I also decided that she wasn’t actually on the conservation commission. She had appointed herself guardian of the character of a neighborhood she didn’t even live in.