George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

Ha ha ha. Clever, but a bit overstated, don’t you think? True, this native speaker of American English (AmE) usually turns the captions on when watching British TV shows like Sally Wainwright’s (awesome) Happy Valley because, between the Yorkshire accent, the colloquialisms, and the speed of conversation, my unaccustomed American ear can miss as much as half of what the characters are saying.

Also true: Accents and colloquialisms can trip me up in AmE as well.

Written English seems to cross the ocean more easily. Accents don’t interfere with the printed page, and print stands still so I can pore and puzzle over anything I don’t get the first time. If I don’t understand a word, I can look it up.

The biography I’m proofreading at the moment is being published simultaneously in the US and the UK. It was written and edited in British English (BrE), so that’s what I’m reading. I have no trouble understanding the text. The big challenge is that I’m so fascinated by the differences between AmE and BrE style, spelling, usage, and punctuation that I have to keep reminding myself that I’m proofreading. “They went to the the museum” is a goof on both sides of the Atlantic and it’s my job to catch it.

I’ve long been familiar with the general differences between BrE and AmE spelling. AmE generally drops the “u” from words like “favour” (but retains it in “glamour,” damned if I know why), spells “civilise” with a “z,” and doesn’t double the consonant in verbs like “travelled” unless the stress falls on the second syllable, as in “admitted.” In BrE it’s “tyre,” not “tire”; “kerb,” not “curb”; “sceptical,” not “skeptical”; and “manoeuvre,” not “maneuver.” (The “oe” in “amoeba” doesn’t bother me at all, but “manoeuvre” looks very, very strange.)

To my eye the most obvious difference between AmE and BrE is the quotation marks. A quick glance at a book or manuscript can usually tell me whether it was written and edited in AmE or BrE. In AmE, quoted material and dialogue are enclosed in double quotation marks; quotes within the quote are enclosed in single. Like this: “Before long we came to a sign that said ‘Go no further,’ so we turned back.” BrE does the opposite: single quotes on the outside, double on the inside.

That part’s easy. What’s tricky is that in AmE, commas and periods invariably go inside the quote marks, but in BrE it depends on whether the quoted bit is a complete sentence or not. If it is, the comma or full stop goes inside the quotes; if it isn’t, the comma or full stop goes outside. What makes it even trickier is that British newspapers and fiction publishers often follow AmE style on this. My current proofread follows the traditional BrE style, and does so very consistently. Thank heavens.

BrE is more tolerant of hyphens than AmE, or at least AmE as codified by Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary and the Chicago Manual of Style and enforced by the copyeditors who treat them as rulebooks. I like this tolerance. (For more about my take on hyphens, see Sturgis’s Law #5.)

BrE also commonly uses “which” for both restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. This also is fine with me, although as a novice editor I was so vigorously inculcated with the which/that distinction that it’s now second nature. Some AmE copyeditors insist that without the which/that distinction one can’t tell whether a clause is restrictive or not. This is a crock. Almost anything can be misunderstood if one tries hard enough to misunderstand it. Besides, non-restrictive clauses are generally preceded by a comma.

In my current proofread, however, I encountered a sentence like this: “She watched the arrival of the bulldozers, that were to transform the neighborhood.” “That” is seldom used for non-restrictive clauses, and a clause like this could go either way, restrictive or non-restrictive, depending on the author’s intent. Context gave me no clues about this, so I queried.

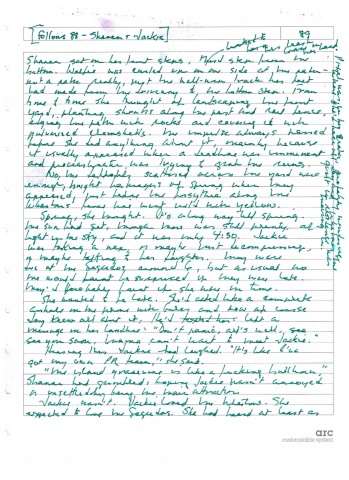

A comma (willing to moonlight as an apostrophe)

Speaking of misunderstanding, remember “I’d like to thank my parents, Ayn Rand and God”? Some copyeditors and armchair grammarians consider this proof that the serial or Oxford comma — the one that precedes the conjunction in a series of three or more — is necessary to avoid misunderstanding. As I blogged in “Serialissima,” I’m a fan of the serial comma, most of what I edit uses the serial comma, but the book I’m proofreading doesn’t use the serial comma and it didn’t me long to get used to its absence.

BrE uses capital letters more liberally than AmE, or at least AmE as represented by Chicago, which recommends a “down style” — that is, it uses caps sparingly. In my current proofread, it’s the King, the Queen, the young Princesses, the Prime Minister, and, often, the Gallery, even when gallery’s full name is not used. Chicago would lowercase the lot of them.

I knew that BrE punctuates certain abbreviations differently than AmE, but I was a little fuzzy on how it worked, so I consulted New Hart’s Rules, online access to which comes with my subscription to the Oxford Dictionaries. If Chicago has a BrE equivalent, New Hart’s Rules is it. In BrE, I learned, no full point (that’s BrE for “period”) is used for contractions, i.e., abbreviations that include the first and last letter of the complete word. Hence: Dr for Doctor, Ltd for Limited, St for Street, and so on. When the abbreviation consists of the first part of a word, the full point is used, hence Sun, for Sunday and Sept. for September.

Thus enlightened, I nevertheless skidded to a full stop at the sight of “B.Litt,” short for the old academic degree Bachelor of Letters. Surely it should have either two points or none, either BLitt or B.Litt.? I queried that too.

AmE is my home turf. I know Chicago cold and can recognize other styles when they’re in play. I know the rules and conventions of AmE spelling, usage, and style, and (probably more important) I know the difference between rules and conventions. In BrE I’m in territory familiar in some ways, unfamiliar in others. I pay closer attention. I look more things up. I’m reminded that, among other things, neither the serial comma nor the which/that distinction is essential for clarity. Proofreading in BrE throws me off-balance. This is a good thing. The editor who feels too sure of herself is an editor who’s losing her edge.

Anna Leahy

Anna Leahy

George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

George Bernard Shaw oh-so-famously said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”