Me and my IWD sign, which says “The common woman is as common as the best of bread / and will rise.” I am, you may have guessed, a regular bread baker. Photo by Albert Fischer.

I’ve been thinking about this because, you guessed it, I recently proofread a book-length collection of poems.

Prompted by the poster I made for an International Women’s Day rally on March 8, featuring a quote from one of Judy Grahn’s Common Woman poems, I’ve also been rereading Grahn’s early work, collected in The Work of a Common Woman (St. Martin’s, 1977). So I’ve got poetry on my mind.

A 250-page book of poetry contains many fewer words than a 250-page work of fiction or nonfiction, but this does not mean that you’ll get through it faster. Not if you’re reading for pleasure, and certainly not if you’re proofreading. With poetry, the rules and conventions generally applied to prose may apply — or they may not. It depends on the poems, and on the poet.

Poetry also offers some tools that prose does not, among them line breaks, stanza breaks, rhyme, and meter. (These techniques and variations thereof can come in very handy for prose writers and editors, by the way.) The work I was proofreading also includes several “concrete poems,” in which the very shape of the poem on the page reflects and/or influences its meaning. “Sneakers” was shaped like, you guessed it, a sneaker; “Monarchs” like a butterfly; “Kite” like a kite.

Errors are still errors, of course. When the name Tammy Faye Baker appeared in one poem, I added the absent k to “Baker” — checking the spelling online, of course, even though I was 99 percent sure I was right. Sometimes a word seemed to be missing or a verb didn’t agree with its subject. In a few cases, the title given in the table of contents differed somewhat from the title given in the text.

Often the matter was less clear-cut. English allows a tremendous amount of leeway in certain areas, notably hyphenation and punctuation, and that’s without even getting into the differences between British English (BrE) and American English (AmE). Dictionaries and style guides try to impose some order on the unruliness, but style guides and dictionaries differ and sometimes even contradict each other.

If you’ve been following Write Through It for a while, you know that I’ve got a running argument going with copyeditors, teachers, and everyone else who mistakes guidelines for “rules” and applies any of them too rigidly. See Sturgis’s Law #9, “Guidelines are not godlines,” for details, or type “rules” into this blog’s search bar.

Imposing consistency makes good sense up to a point. For serial publications like newspapers or journals, consistency of style and design helps transform the work of multiple writers and editors into a coherent whole. But each poem is entitled to its own style and voice, depending on its content and the poet’s intent. Short poems and long poems, sonnets, villanelles, and poems in free verse, can happily coexist in the same collection.

What does this mean for the proofreader? For me it means second-guessing everything, especially matters of hyphenation and punctuation. Remember Sturgis’s Law #5? “Hyphens are responsible for at least 90 percent of all trips to the dictionary. Commas are responsible for at least 90 percent of all trips to the style guide.”

But dictionaries and style guides shouldn’t automatically override the preferences of a poet or careful prose writer. The styling of a word may affect how it’s heard, seen, or understood. When I came upon “cast iron pot,” my first impulse was to insert a hyphen in “cast-iron,” and my second was No — wait. Omitting the hyphen does subtly call attention to the casting process; my hunch, though, based on context, was that this was not the poet’s intent. I flagged it for the poet’s attention when she reads the proofs.

Another one was “ground hog.” I can’t recall ever seeing “groundhog” spelled as two words, though it may well have been decades or centuries ago. However, in the first instance “ground hog” broke over a line, with “ground” at the end of one line and “hog” at the beginning of the next. In prose such an end-of-line break would be indicated with a hyphen, but this poet generally avoided using punctuation at the ends of lines, instead letting the line break itself do the work, except for sentence-ending periods. “Ground hog” recurred several times in the poem, so consistency within the poem was an issue. It was the poet’s call, so again I flagged this for her attention.

One last example: Reading aloud a poem whose every line rhymed with “to,” I was startled to encounter “slough,” a noun I’ve always pronounced to rhyme with “cow” (the verb rhymes with “huff”). When I looked it up, I learned that in most of the U.S. “slough” in the sense of “a deep place of mud or mire” (which was how it was being used here) is indeed generally pronounced like “slew.” The exception is New England, which is where I grew up and have lived most of my life. There, and in British English as well, “slough” often rhymes with “cow” in both its literal and figurative meanings. (For the latter, think “Slough of Despond.”)

All of the above probably makes proofreading poetry seem like a monumental pain in the butt, but for me it’s a valuable reminder that English is remarkably flexible and that many deviations from convention work just fine. At the same time, although I can usually suss out a writer’s preferences in a book-length work, I can’t know for sure whether an unconventional styling is intentional or not, so sometimes I’ll query rather than correct, knowing that the writer gets to review the edited manuscript or the proofs after I’m done with them.

The other thing is that while unconventional stylings may well add nuance to a word or phrase, they rarely interfere with comprehension. Copyeditors sometimes fall back on “Readers won’t understand . . .” to justify making a mechanical change. When it comes to style, this often isn’t true. My eye may startle at first at an unfamiliar styling or usage, but when the writer knows what she’s doing I get used to it pretty quickly.

The above examples come from Mary Hood’s All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, forthcoming this fall from Shade Mountain Press. It’s a wonderful collection, and I highly recommend it. Established in 2014, Shade Mountain Press is committed to publishing literature by women. Since it’s young, I can say that I’ve read and heartily recommend all of their titles, which so far include three novels, a short-fiction anthology, and a single-author collection of short stories. All the Spectral Fractures is their first poetry book. I rarely mention by title the books that I work on, but Rosalie said it was OK so here it is.

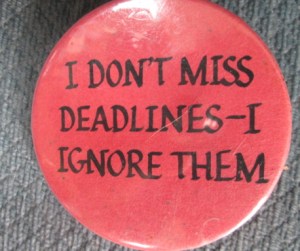

Most editors and writers have mixed feelings about deadlines. We love them when we’ve met them, not least because if this is a paid gig the check will shortly be in the mail or payment will land in our bank account.

Most editors and writers have mixed feelings about deadlines. We love them when we’ve met them, not least because if this is a paid gig the check will shortly be in the mail or payment will land in our bank account.

This morning I deleted chapter 4. Selected the whole damn thing and zapped it. The old chapter 5 is the new chapter 4. Viva chapter 4!

This morning I deleted chapter 4. Selected the whole damn thing and zapped it. The old chapter 5 is the new chapter 4. Viva chapter 4!