Writers may write in solitude, but there’s nearly always at least one other person in the room. Maybe we see them. Maybe we don’t. Maybe we see them but try to ignore their existence. Maybe they’re in our own head.

Readers.

Editors are test readers of writing that hasn’t gone out into the world yet. Our job is to help prepare the writing for its debut. We’re hired because we’re adept in the ways of spelling, punctuation, grammar, usage, structure, and so on, but on the other hand we’re supposed to be professionally stupid: if the writing isn’t clear enough, if gaps and inconsistencies exist in the sentences and paragraphs we’re reading, we aren’t supposed to fill them in from what we already know. The writing is supposed to do the work.

This is fine as far as it goes, but sometimes editors forget that despite our expertise and the fact that we’re getting paid, we can’t speak for all readers. If an editor tells you that “readers won’t like it if you . . .” listen carefully but keep the salt handy: you may need it. Editors should be able to explain our reservations about a word or a plot twist or a character’s motivation without hiding behind an anonymous, unverifiable mass of readers.

One of the big highs of my writing life was when my Mud of the Place was featured by the several Books Afoot groups who traveled to Martha’s Vineyard in 2013 and 2014.

Readers can and often do take very different things away from the same passage, the same poem, the same essay, the same story. At my very first writers’ workshop (the 1984 Feminist Women’s Writing Workshop, Aurora, New York), day after day I listened as 18 of us disagreed, often passionately, about whether a line “worked” and whether a character’s action made sense or not and whether a particular description was effective or not. It was thrilling to see readers so engaged with each other’s work, but also a little unsettling: no matter how capable and careful we writers are with our writing, we can’t control how “readers” are going to read it.

This is a big reason I advise writers to find or create themselves a writers’ group — and to develop the skill and courage to give other writers their honest readings of a work in progress. This may be the greatest gift one writer can give another.

I just came to “Teasing Myself Out of Thought” in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Words Are My Matter: Writings About Life and Books, 2000–2016 (Easthampton, MA: Small Beer Press, 2016), and what do you know, it articulates eloquently and clearly some of what I’m feeling my way toward here.

“Most writing is indeed a means to an end,” she writes — but not all of it. Not her own stories and poems. They’re not trying to get a point across: “What the story or the poem means to you — its ‘message’ to you — may be entirely different from what it means to me.”

She compares “a well-made piece of writing” to “a well-made clay pot”: the pot is put to different uses and filled with different things by people who didn’t make it. What she’s suggesting, I think (maybe because I agree with her), is that readers participate actively in the creation of what the story or poem means. Readers are “free to use the work in ways the author never intended. Think of how we read Sophocles or Euripides.” What readers and playgoers have discovered in the Greek tragedies has evolved considerably over the last 3,000 years, and it’s a good guess that Sophocles and Euripides didn’t embed all those things in their works.

“A story or poem,” writes Le Guin, “may reveal truths to me as I write it. I don’t put them there. I find them in the story as I work.”

If this reminds you of “J Is for Journey,” it does me too. And notice where that particular blog post started.

And finally this: “What my reader gets out of my pot is what she needs, and she knows her needs better than I do.”

That’s a pretty amazing and generous statement, and one editors might consider occasionally, especially when we’re editing works that aren’t simply means to an end.

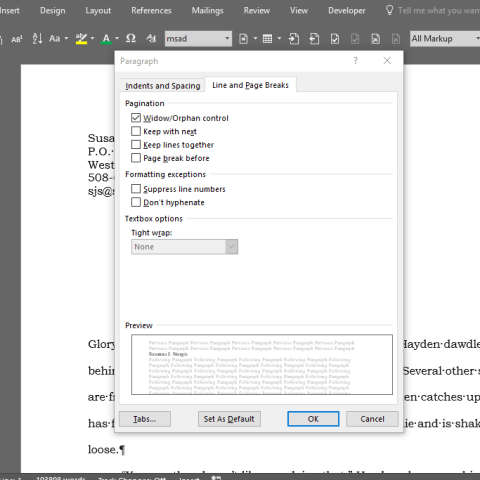

Hell, I even query myself. A lot. Every draft of my every manuscript has got queries in it: comments from members of my writers’ group, thoughts that have occurred to me while writing, rereading, or walking with the dog. Mostly I’m pretty tactful in those queries to myself, but sometimes you can tell I’m getting exasperated.

Hell, I even query myself. A lot. Every draft of my every manuscript has got queries in it: comments from members of my writers’ group, thoughts that have occurred to me while writing, rereading, or walking with the dog. Mostly I’m pretty tactful in those queries to myself, but sometimes you can tell I’m getting exasperated.

In other words, value judgments lurk not far below the surface of both “literary” and “literature,” and it’s not hard to see how they stir up uneasiness and outright opposition. In some quarters “literary” suggests not only bookish and pedantic, but pretentious, snobbish, affected, esoteric, incomprehensible . . .

In other words, value judgments lurk not far below the surface of both “literary” and “literature,” and it’s not hard to see how they stir up uneasiness and outright opposition. In some quarters “literary” suggests not only bookish and pedantic, but pretentious, snobbish, affected, esoteric, incomprehensible . . . Genres have been around long enough at this point that they’re embedded in readers’ heads. Audiences have developed for particular genres, subgenres, and sub-subgenres, and self-publishers who want to sell ignore this at their financial peril.

Genres have been around long enough at this point that they’re embedded in readers’ heads. Audiences have developed for particular genres, subgenres, and sub-subgenres, and self-publishers who want to sell ignore this at their financial peril.

Not to worry about all this flux and multiplicity, at least not too much. A couple of things to keep in mind, however, when someone accuses you or not knowing your grammar or when, gods forbid, you are tempted to accuse someone else: (1) spelling and punctuation are not grammar, and (2) some of the rules you know are bogus.

Not to worry about all this flux and multiplicity, at least not too much. A couple of things to keep in mind, however, when someone accuses you or not knowing your grammar or when, gods forbid, you are tempted to accuse someone else: (1) spelling and punctuation are not grammar, and (2) some of the rules you know are bogus. In the Age of Google, you can find almost anything on the Web, but plenty of it hasn’t been subjected to either fact-checking or editing. As you’ve probably learned for yourself, verifying the attribution of a quotation is a particular challenge because misattributions seem to multiply exponentially — giving rise to memes like the classic at left (variations of which have also been attributed to Mark Twain, among others).

In the Age of Google, you can find almost anything on the Web, but plenty of it hasn’t been subjected to either fact-checking or editing. As you’ve probably learned for yourself, verifying the attribution of a quotation is a particular challenge because misattributions seem to multiply exponentially — giving rise to memes like the classic at left (variations of which have also been attributed to Mark Twain, among others). In this age of spin and “fake news” each of us has to do our own fact-checking. Because we rarely have the time or inclination to check every fact, we generally focus on the source, the news outlet: if it’s got a good track record, it’s probably because its reporters, editors, and fact-checkers are on the ball. When they screw up, our faith is shaken. Was this an aberration, or are they going down the tubes?

In this age of spin and “fake news” each of us has to do our own fact-checking. Because we rarely have the time or inclination to check every fact, we generally focus on the source, the news outlet: if it’s got a good track record, it’s probably because its reporters, editors, and fact-checkers are on the ball. When they screw up, our faith is shaken. Was this an aberration, or are they going down the tubes?